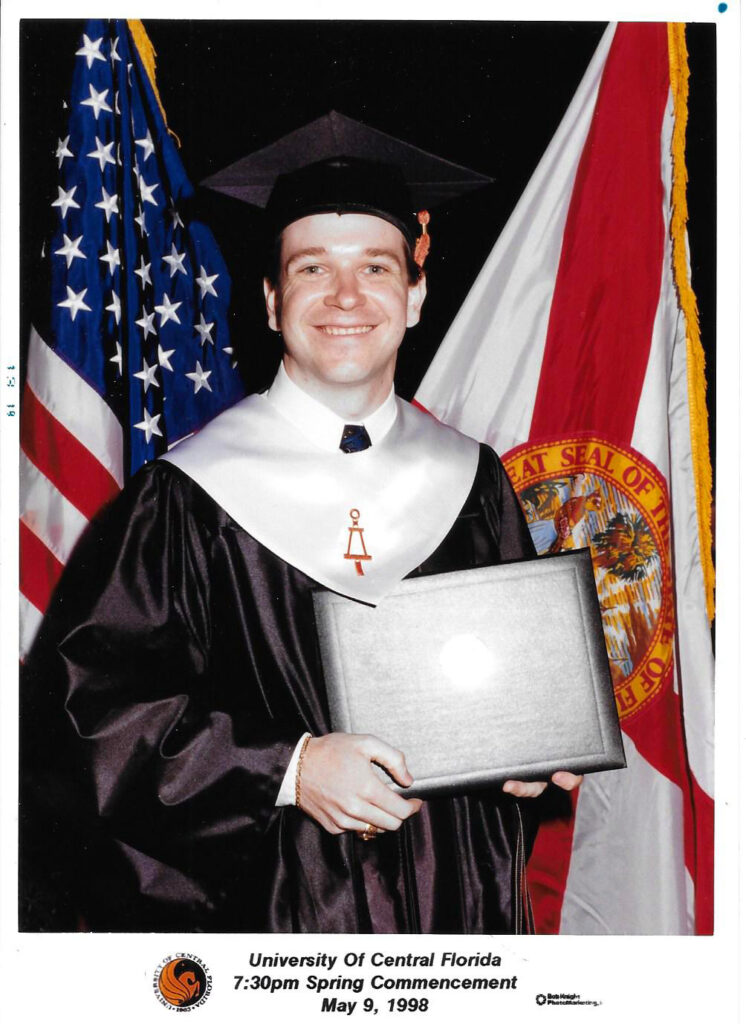

Andrew Downing ’98 Receives First Patent for His Work at Lockheed Martin

By Camille Dolan ’98

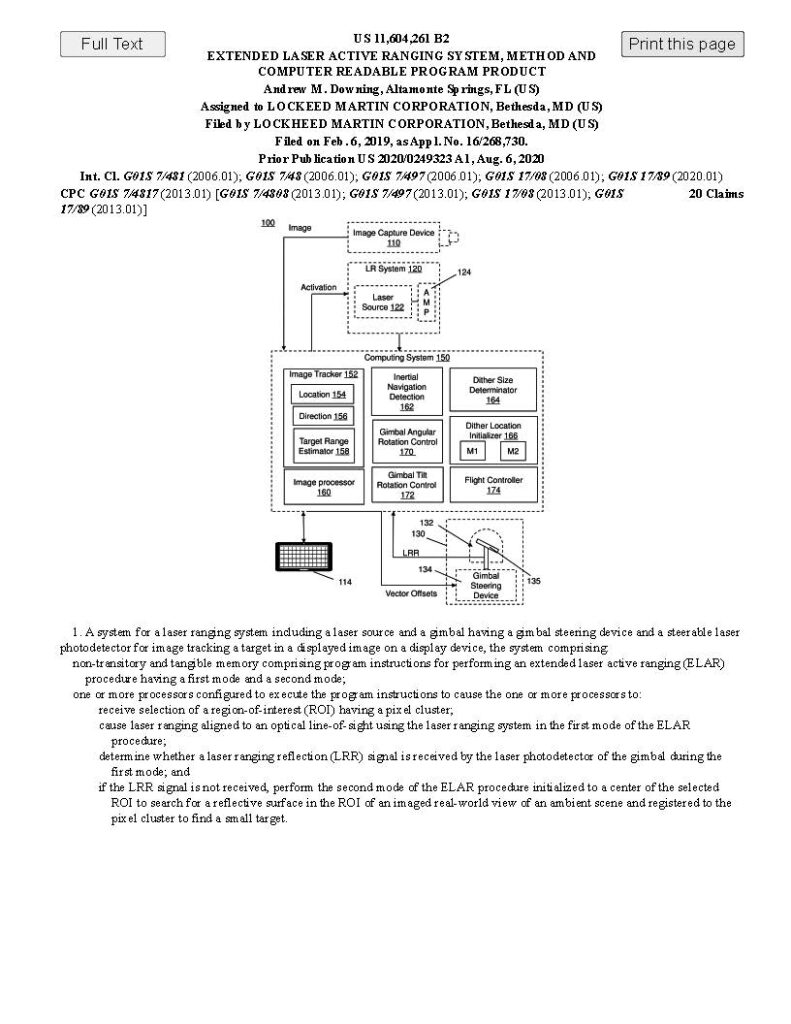

Andrew Downing ’98, a 25-year employee for Lockheed Martin, recently received notification he has been granted a patent for his “Extended Laser Active Ranging System, Method and Computer Readable Program Product.”

Downing was the lead investigator on the technology, which began development in 2017 and commenced flight testing in Fall 2018. Because of the efficacy of Downing’s invention, Lockheed Martin implemented the product.

“The novelty of the design showed laser-ranging at longer distances can be achieved without increasing laser-output power or more expensive detectors,” Downing says, “And the design granted more capability to our customers with no additional program cost.”

The Long Road from UCF to Patent Awardee

Receiving his first patent was a cause for celebration for Downing; his invention becomes the intellectual property of his employer, which is standard business practice.

“After working on something for more than six years and facing the possibility that my work would be discounted or ignored, this is a huge validation for my life’s work,” Downing says.

It’s a career that Downing says was made possible through his time at UCF.

Growing up in Wichita, Kansas, Downing thought he was destined for a career as a draftsman. A draftsman makes detailed technical drawings or plans for machinery, buildings, electronics, infrastructure, etc. Downing, who was good at math and science, was initially drawn to the field by default.

A little history: Wichita is a hub for the aerospace industry, largely due to Clyde Cessna, a farmer from nearby Rago who, in 1911, built his own plane and quickly launched an airplane manufacturing business, and from there the city grew to claim the lofty title of “Air Capital of the World.”

A ‘Bored’ Student Finds His Passion

“I grew up around the aircraft and defense industry,” Downing says. “And I started college in town, but I didn’t like it because I was too close to home, and I was bored.”

He dropped out of college and wanted to start a career, and easily landed a job at a drafting firm in Wichita. One of his colleagues, who happened to be an engineer, took him aside.

“He told me that I had the intelligence to go a lot further than just being a draftsman,” Downing recalls.

Downing had started drafting on paper, but as the firm began transitioning toward computers, the engineer noticed his agility with the technology and told him something that changed his life.

“’Andrew, you could work here for four years and get four dollars more an hour, or you could go get a higher degree and make a lot more.’”

The advice was powerful.

Downing on Path to UCF

“He was a good motivator,” Downing says. So, Downing packed his bags and went south to what was then Seminole Community College. As he began learning more about engineering, he soon realized that he would need a four-year degree and applied to a “bunch” of colleges.

Fortunately for UCF, we recognized talent when we saw it, and aggressively pursued Downing to come tour the campus, and to learn about our own growing connection to the aerospace industry.

“UCF was very interested in having me as a student,” Downing says.

He started studying electrical engineering as a junior, and also started working at Florida Solar Energy Center. FSEC is the state’s premiere energy research institution and was created by the Florida Legislature in 1975 to advance research, development and education in solar energy.

“I was a research assistant there, and I was doing 3D modeling for them,” Downing says. “They were working on solar energy research and energy efficient housing.”

At the time, Downing worked under the direction of Subrato Chandra, Ph.D., a research engineer at Florida Solar Energy Center for over 30 years. He was recognized by the state of Florida as a distinguished and meritorious researcher in energy efficient housing before his death in 2012.

“Dr. Subrato really helped me understand the importance of research and that whole process,” Downing says “He recommended that my supervisors send me to Tampa to learn 3D modeling. So here I was, taking classes as a student, and as a research assistant, I’m doing 3D modeling for the Solar Energy Center. It was a great experience for me.”

Downing was experiencing none of the boredom that he had felt taking college classes in Wichita. He started to see possibilities.

Downing says Subrato was instrumental in helping him understand how things work.

“Dr. Subrato and my professors at UCF really gave me the building blocks to have a great career,” Downing says.

He also built a strong social network that continues to this day by joining the UCF Gaming Club where, in his free time, enjoyed chess, board gaming and strategy gaming.

“I had a lot of fun and graduated,” Downing says. “And when I did, I had five offers because the internet boom was happening, and anyone with an engineering degree was needed. I took a hardware job, and a lot of the job offers I had received were in software.”

Downing Launches Career at Lockheed Martin

As an electrical engineer who had aptitude in electrical engineering and computer science, Downing wanted a traditional engineering job. His career became full circle, and he took a job in Lockheed Martin. He has been working in missiles and fire control ever since graduation.

Downing has designed many circuit boards since he’s been at Lockheed Martin.

“It’s like building a miniature city,” Downing says. “In SimCity, for example, a player can place all the buildings and little roads and introduce simulation. We do the same thing in electrical engineering.”

In board design, however, there are hundreds of components on a single board, and that the processors and the amplifiers are going back and forth between the microchips, and instead of, perhaps, building a bridge in SimCity, Downing’s boards, in some cases, are used in aircraft and helicopters.

“I designed a chassis that would interface with our products and the rest of the aircraft, and you know, route video signals from one location to another to control various mechanisms,” Downing says. His boards have to have their own power supplies, which also need to be designed.

In theory, Downing adds, “you can design a board on a napkin in one day, and say, OK, this needs to route this way, this needs to route that way, and then you spend the next year designing individual components in that board and justifying the design to make sure that it’s reliable, good quality, has the right power, the right processing, etc.”

An Engineer and a Mentor

The ease with which Downing explains difficult engineering concepts has made him a sought-after mentor at Lockheed Martin. He is currently mentoring Sophie Dickey, a UCF environmental engineering student who is graduating this fall, but he has had multiple UCF interns.

“I really enjoy mentoring, probably because I did so much mathematics and science tutoring in college,” Downing says. And recently, when a friend asked him if he could help his child with an algebra course, he stepped in.

“It is such a great moment when that light bulb turns on,” Downing says. “When they can achieve an A or B in class when they were getting Cs and Ds.”

Those little wins that Downing is able to inspire in his mentees and tutees mirror the satisfaction that he himself has received from acknowledgment of his first patent.

Proud to be a UCF Knight

“This is really a personal achievement for me,” Downing says. “I can potentially go get another patent, but it’s the simple fact that I got my first one just really makes me happy. To be recognized as an engineer for the hard work that we do and realizing that we can make a difference in the world means a lot to me. And especially to look back as a UCF alumnus and know that this success would not have been possible without my education here, it just makes me proud to be a Knight.”